|

Like many organizations this summer, the Guild of Natural Science Illustration held their annual conference virtually this past weekend. While we all wished we could have been together, being virtual means a lot more people can participate in the event and also view the beautiful and varied artwork in this year's exhibit online. I am fortunate to have one of my pieces selected for the juried exhibit. Check out the link to see all of the wonderful scientific illustration: 2020 GNSI MEMBER EXHIBITION

1 Comment

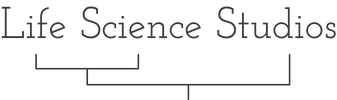

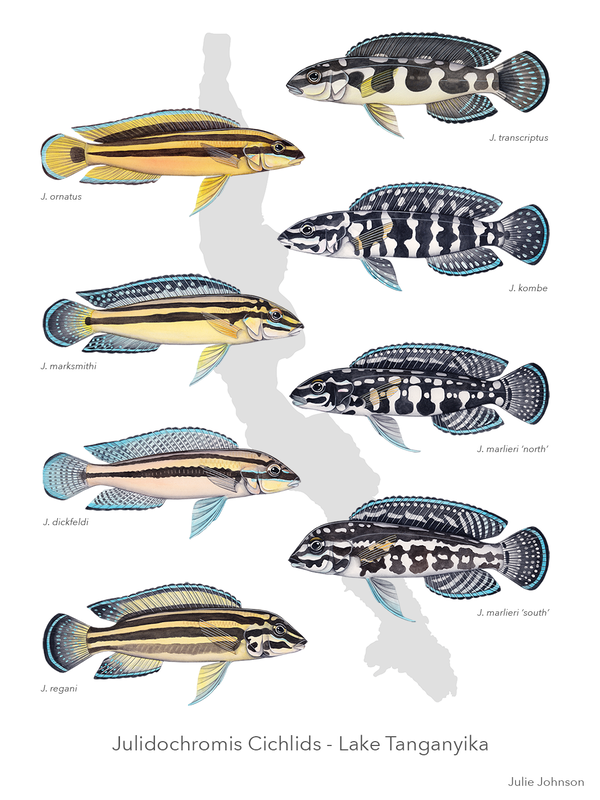

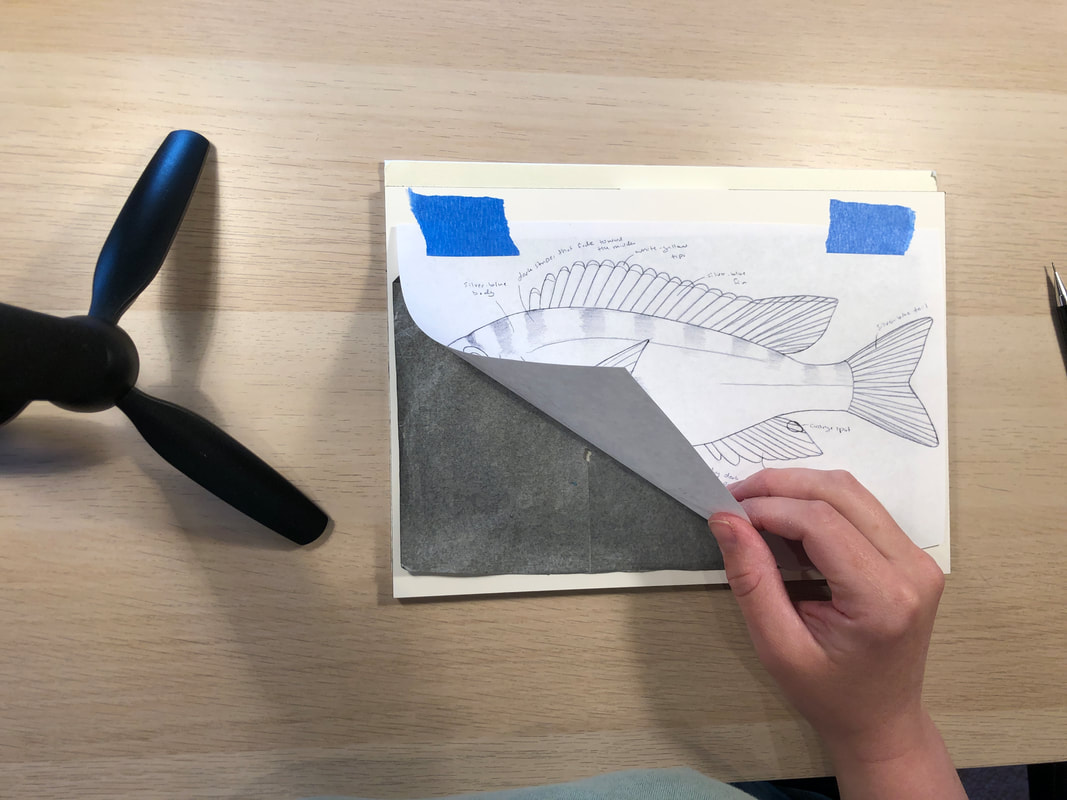

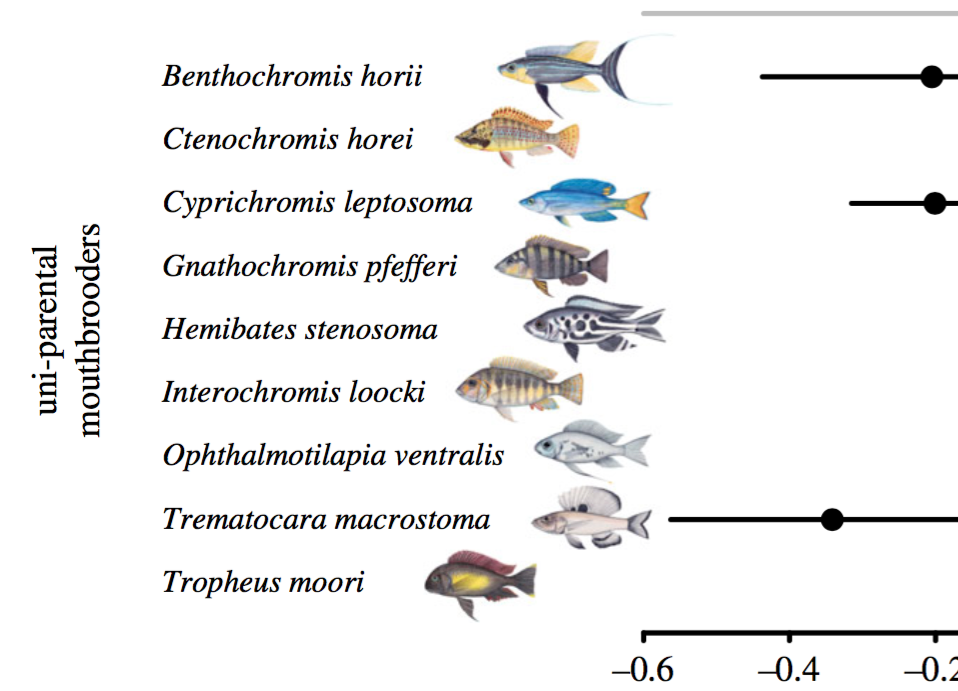

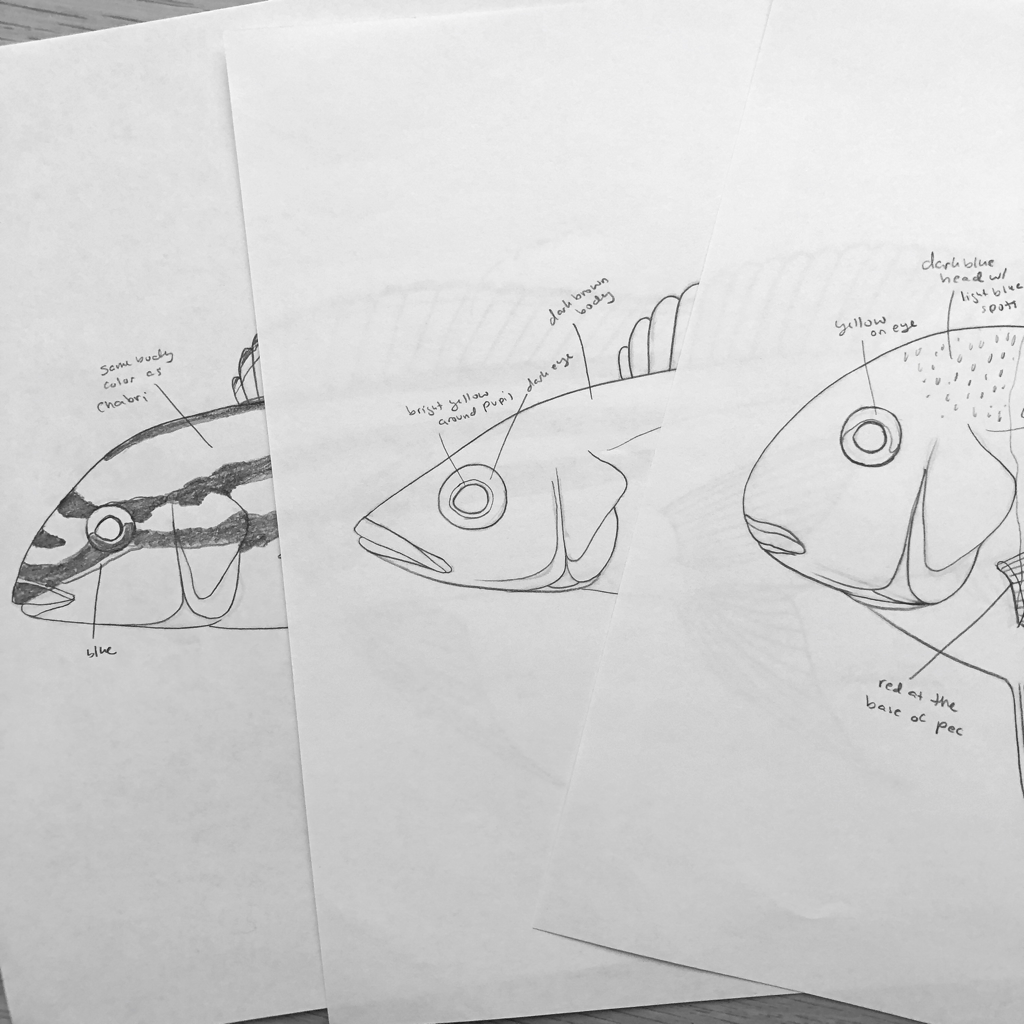

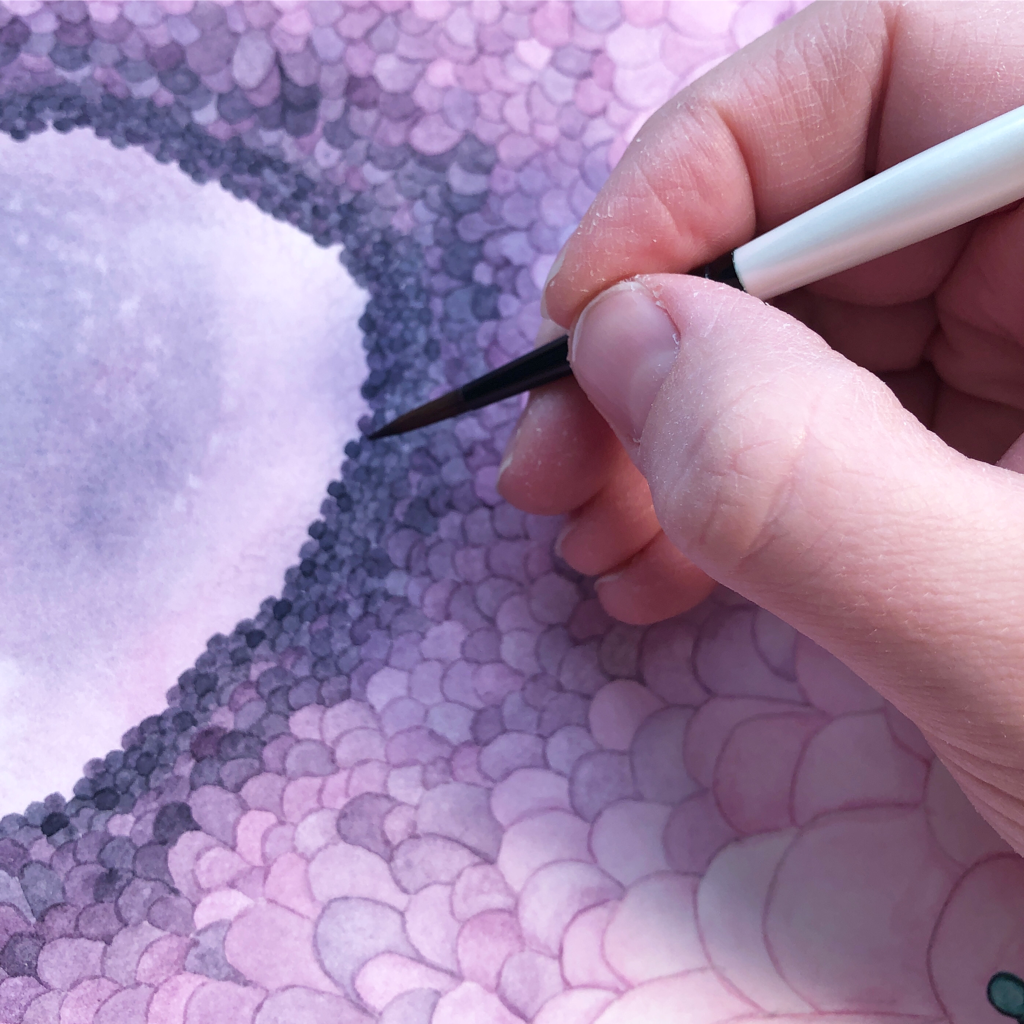

For the last few years, I have been painting all 250+ cichlid fish species in Lake Tanganyika for Walter Salzburger's lab in Switzerland. Through this project, I've learned a few things about how to paint fish, and I thought I would share my process! Step 1: Transfer the sketchI use reference photos, specimens, and feedback from working closely with experts to create the sketch. Once the sketch is finished, I then have to transfer it onto watercolor paper. For this step, I tape the sketch on the watercolor block, place a piece of carbon paper underneath, and trace the lines. The pressure from the pencil causes the carbon to deposit onto the watercolor paper. Step 2: Trace back over the sketchThe carbon sketch ends up being kind of fuzzy and smudgy, so the next step is to use a kneaded eraser to remove some of the carbon so that there is just a light shadow of all of the lines. Then I go back over all of the lines with a very light pencil. Note: most of these videos will be time-lapse. I don't actually work this fast! Wouldn't it be awesome if I did. Step 3: Fill in the base colors and shadingNow I can start painting! I add all of the base colors and shading on the body and fins. I like to use a combination of grays and purples to add shadows to the body and give it a three-dimensional shape. (I also paint the eye pretty early in the process because adding an eye makes the fish look more alive, and for whatever reason, I find it easier to paint the fish when it looks like it has some personality.) STep 4: Paint the linesNext, I use a small brush to add the lines that make up all of the fins. I always leave the pectoral fin for one of the last steps because any additional painting I do on the body would smear or fade the pectoral fin. Step 5: Shade the FinsI now use some darker grays and purples to add shading to the fins and body. This is the step that really brings definition to each of the rays and makes the fins look more realistic. Step 6: Add in the stripes and spotsStripes and spots can be tricky. In some species of cichlid, the stripes are very well defined and will have a clean edge. For those, I can just put some paint on my brush and paint the stripes. But other cichlids, like this one, have more subtle markings that don't have a strong edge. For these, I put down a layer of water first, and then add paint on top. The water layer allows the paint to diffuse and give a more faded effect. Step 7: Put in a few HighlightsAfter I've painted the stripes, I add the lines to the pectoral fin (oops I forgot to video that part). The next thing to do is add highlights. This is my favorite part. I use white gouache, which is an opaque water-based paint, to add some shiny areas. This really brings the painting to light and makes it look polished and complete. Step 8: Finishing touchesI'm almost done! The very last thing to do to this painting is add in a few scales. These paintings are going to be reproduced pretty small in publications, and adding every single scale would result in a much more complicated painting that would look messier. So I have chosen to paint most of these fish with a hint of scales by adding some darker or lighter patches. I then scan and edit the painting digitally and submit them to be used in publications and presentations!

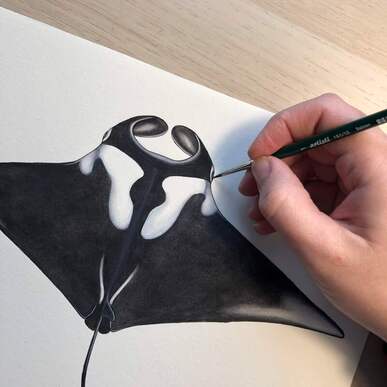

How do you communicate your research when photos of your study species are impossible to obtain or contain sensitive material? An illustrator can help create beautiful objective imagery when photos can't be used. This scenario happened with Ph.D. candidate, Melissa Cronin at UC Santa Cruz. Melissa works with manta and devil rays, and her work focuses on understanding the life history of these giant animals and working with the tuna industry to reduce the impact of by-catch on manta mortality. She needed visuals to use for communicating her research that would also serve to help with species identification. The first problem: these are massive animals. Manta rays can get to be 23 feet across and 6,600 lbs! Many of the mobulid ray species live in pelagic offshore habitats where they aren't often seen by humans, so photographing something this huge, underwater, in the open ocean, is simply impossible for her to do. The second problem: many of the photos of these rays are from by-catch. The animals are in distress and the photos cause viewers to bring in an emotional response that distracts from focusing on the details of the research findings. The Solution: Work with a science illustrator! Melissa and I talked about what she needed, and she sent me photos, videos, pages from guidebooks, and resources I would need to make her paintings. I then created these ten watercolor and gouache paintings for her. Now, she has illustrations she can use in her talks and to help with species identification and research. The artwork is clearer and more objective than the available photos. I hope my illustrations help her achieve her research goals and help conservation efforts for these magnificent animals. To learn more about Melissa's work, check out https://ccal.ucsc.edu/melissa-cronin/

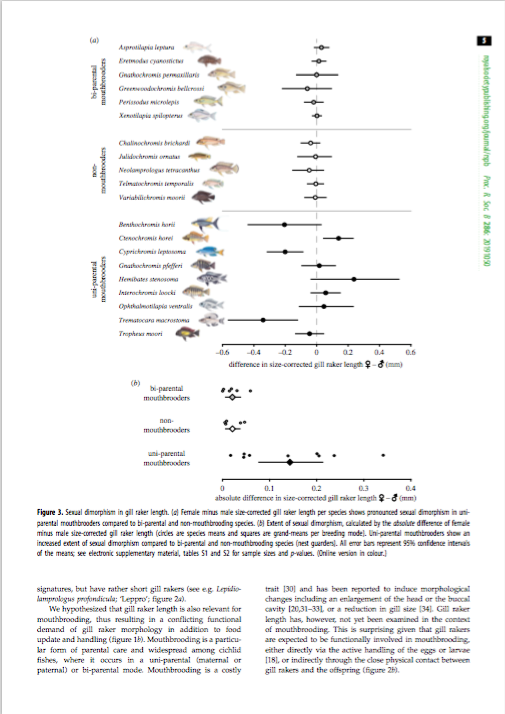

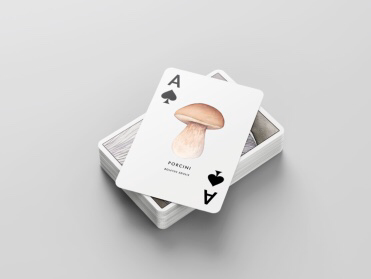

We are living in strange times now. I am so thankful that I normally work from my home studio and that my clients are all remote anyway. It makes it much easier to continue doing science illustration. I am still open for business, making new products, creating new artwork, and taking on new clients and projects. Life Science Studios has moved locations! I am now operating out of Bellingham, WA, in a new studio room with an inspiring view. I have added a couple of fun new products to the shop. You may have also noticed that you can now purchase mushroom art products directly from the Life Science Studios website. I am so excited to have my own store on my website now! You can also still purchase through Etsy. A few of my cichlid fish paintings have been published in research journal articles. I love seeing how the paintings and data work together to communicate the research findings. I have two more papers featuring my artwork coming out soon, and I can't wait to share those! I also had a great time creating a new logo for The Hungry Forager, a new company out of Kentucky. The client wanted a logo for the website and a circular one for social media, so we came up with two fun versions. The logos show the variety of foraged foods that The Hungry Forager will be selling. I hope you all are safe and healthy and staying home.

It's March! And March has everybody thinking green, for St. Paddy's Day. So I thought I would profile my favorite green mushroom, Gliophorus psittacinus, known as the Parrot Wax Cap. This tiny mushroom is hard to miss because of its bright BRIGHT green color and super slimy cap! When I lived in California, I used to find these in the redwood forests near Santa Cruz. They are so beautifully bright green against the red-brown background of the redwoods. This species also comes in bright red-orange and bright yellow too! Key CharacteristicsCap: The cap is smooth, convex, and covered in slime. The color ranges from bright green to dark green when young, and changes to shades of pink, yellow, and orange with age.

Hymenium: The gills are adnate to subdecurrent, occasionally seceding. Color is greenish when young, becoming concolorous with the cap in age. Stipe: The stipe is cylindrical to tapered up. It is greenish when young, becoming yellow, orange, or pink with age. Spore Print: White Ecology: Mycorrhizal Mushroom playing cardsI am thrilled to announce a new collaboration with MyComestible! We are bringing you playing cards featuring mushroom watercolor paintings. Each deck has 54 wild edible species; one deck for North American mushrooms (in English) and the other for European mushrooms (in French). The pre-sale starts today! Get yours for a discounted price only in the month of March. Visit www.mycomestible.com.

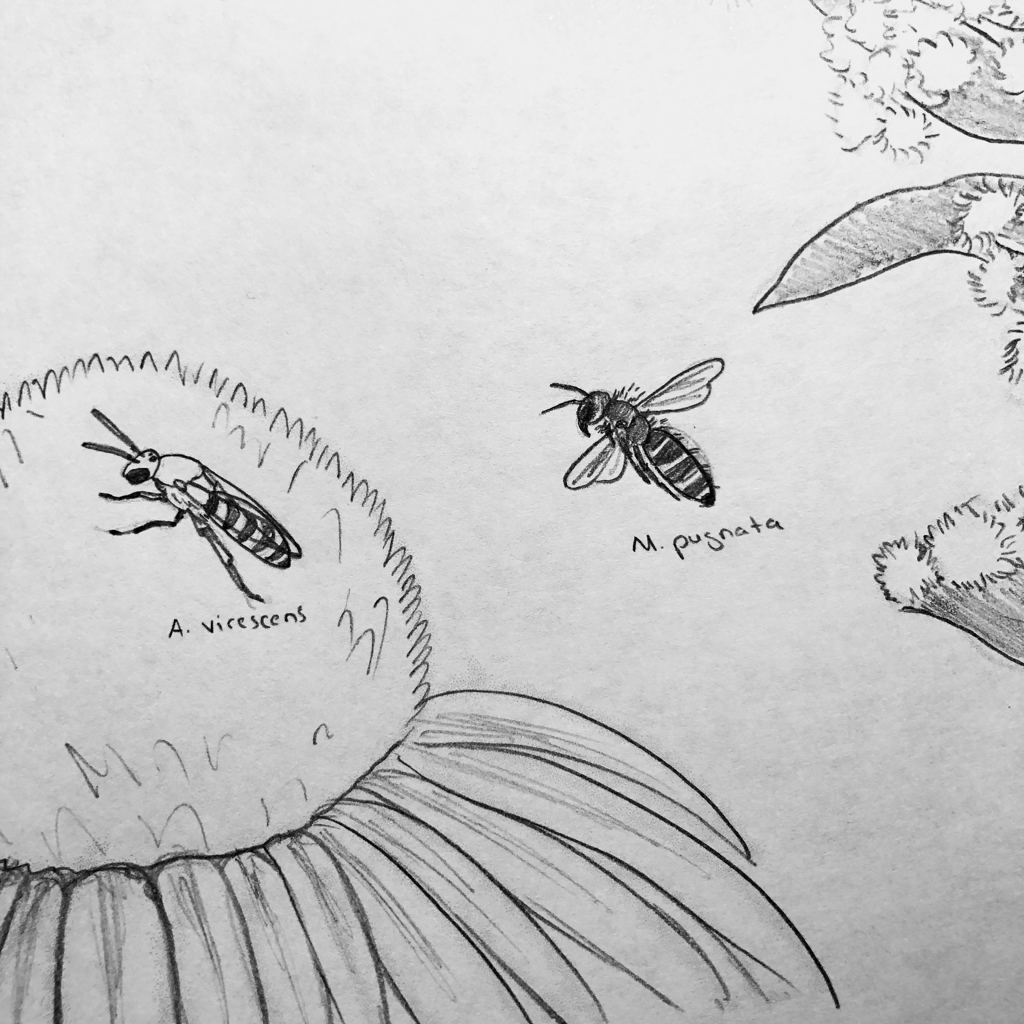

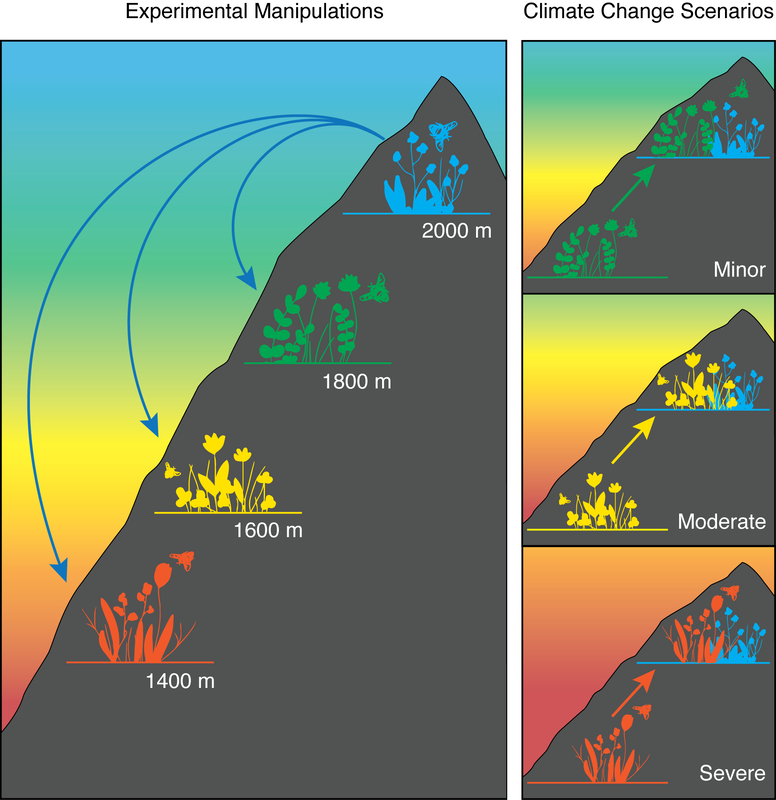

There are tons of ongoing projects happening at Life Science Studios. My to do list of paintings was 63 at the end of January and has now shrunk to 29. Whew! Here is an update on a few of those projects: Tanganyikan CichlidsI am getting so close to finishing paintings of all of the cichlid fish species of Lake Tanganyika, and there are a lot of them! This week, I spent some time working on sketches of fish for which we have very little (sometimes zero) reference images or information. It's tricky, but having done hundreds of these fish already, I have become pretty good at interpreting how a fish should look, even based on a poorly preserved specimen or blurry photo. I'm looking forward to painting a few of these sketches next week. Mobulid RaysThis week, I painted a number of mobulid (manta and devil) ray species for a client at UC Santa Cruz who studies these beautiful creatures. These paintings have been so fun to do, and a bit difficult because of the subtle shading and markings on some of them. I am looking forward to seeing my client use these in her work, and I think they will do a lot to enhance her message. Bees and More BeesBees have a very special place in my heart, so I am excited to be working on two different bee projects! One of them is for interpretive panels here at Princeton University campus and the other is for an upcoming scientific paper. The interpretive panels will be created using watercolors, while the journal figure is done entirely digitally. MushroomsLife Science Studios has a new collaboration! I have been painting tons of new mushroom species for this project, and this Sunday, I will have a big announcement about the launch of Mycomestible. Stay tuned! New From the ShopI share a home office with an ecologist. My husband is a research associate at Princeton University, and his home desk is right next to mine. This means that I often look over my shoulder and end up saying "are you publishing your figure like that? What does it even mean? Hold on, let me see what I can do." This happened the other day as he and his collaborators were finishing up a really exciting experiment they had recently completed in the Swiss Alps. This experiment involved moving entire plant communities down mountains in order to see how the plant-pollinator interactions would change under climate change. As the world warms, alpine plants would experience warmer temperatures. Moving the plants down the mountain is a super clever way of warming them and simulating climate change. The challenge was to create a figure that showed communities moving downslope and the different climate change scenarios faced by alpine plants. Here is the first version of the figure: This figure shows plants being transplanted downslope, where they will experience warmer temperatures. And then migrating upslope to escape hot temperatures as the climate warms from minor to moderate to extreme. As he explained the figure to me, it was clear that there were some things I didn't understand and that didn't make sense to me from what the figure showed. It is always a good idea to get fresh eyes on a figure because often the scientist is so familiar with the work that they become too close to the project and can't see what it looks like to someone reading this for the first time. Here is what I came up with: This figure now shows the mountain slope and different plant communities with pollinators, to give the reader context. The colors more accurately represent a conventional heat gradient and match the colors of each plant community. By creating the big panel on the left, showing the Experimental Manipulation, it gives context to the smaller panels on the right, showing Climate Change Scenarios. As the climate warms, those warmer zone communities will be forced to move up the mountain to escape the heat and will interact with colder zone communities. Showing the communities overlapping helps the reader understand the novel environment in which these species will exist.

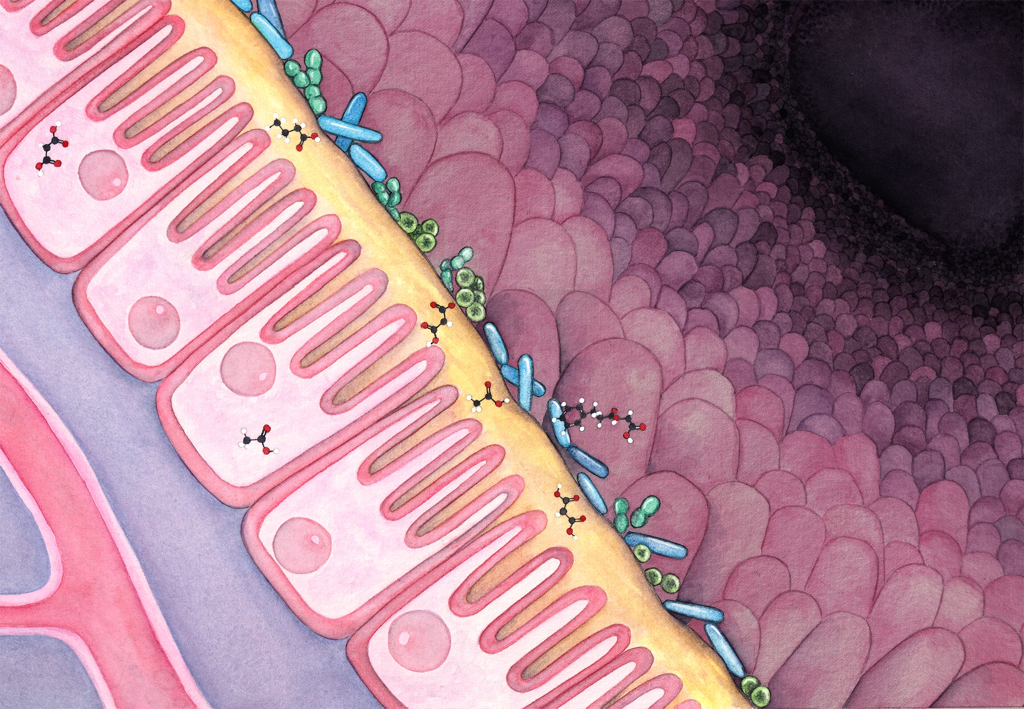

This new illustration was added to the final paper, which just was published this week in Global Change Biology. This type of work is where science illustrators can make a big difference for scientists. By sitting down with an artist, the scientist can communicate the main message and the most important aspects of a figure, allowing the artist to bring a visual language to the figure and communicate the science more effectively to the reader. This is especially important for very complicated experiments or concepts where the diagrams are often a more effective form of communication than writing. So when your schematic looks erratic, enigmatic, or problematic, consider hiring an illustrator who can make it more dramatic, diagrammatic, and even polychromatic. Check out the really cool and important work done by these scientists. Their paper is: Asynchronous range shifts drive alpine plant-pollinator interactions and reduce plant fitness by Sarah K. Richman, Jonathan M. Levine, Laura Stefan, and Christopher A. Johnson in Global Change Biology. If you’ve looked at my portfolio, you are probably surprised to see me painting something microscopic! I recently had the opportunity to create this piece for the launch of a brand new company, DeepBiome Therapeutics. This innovative company is studying the human gut microbiome to create novel drugs and therapies. Hiring a science illustrator was the best way to depict their company’s mission. The founders wanted an eye-catching image showing the interaction of bacteria with the human intestines. I worked closely with the scientists to come up with this painting of bacteria on a mucus layer coating the microvilli, and placed in the context of a sea of intestinal villi. The way the villi fade into a dark mysterious space is meant to play off the title of their article, “Inventing Medicine by Accessing the Hidden Treasure in the Human Microbiome’s Dark Matter.” This is not the first time I have illustrated for a company such as DeepBiome. I also did a handful of illustrations for the blog articles of a human skin microbiome company, Mother Dirt. For companies that work with microbes, science illustration can be a valuable tool in telling their story and reaching a wider audience. The interactions I have depicted are impossible to capture in a photograph or under a microscope. The artistic interpretation allows me to play with the scale of things and show molecules next to structures that are much larger, like villi. I hope I will have the opportunity to do more work like this in the future. I have loved bacteria ever since working as a lab manager for a microbiology class where I spent every day growing cultures. Microbes are so fascinating, and I enjoyed the chance to learn more about them through this project.

This month, I am featuring one of my favorite edible species. Craterellus cornucopioides is commonly called the Black Trumpet or Horn of Plenty fungus. In France, they call it trompettes-des-morts, which translates as "trumpet of the dead". But do not be fooled by the ominous names! This little fungus is delicious and safe to eat. Craterellus cornucopioides has a thin skin that is dark brown or black on top and lighter gray underneath. It can be very difficult to find because it blends in with sticks and leaf litter so well. In fact, I have been hunting for these with a group of people where everybody walked by a large cluster of these right next to the trail. Luckily the last person in line spotted what we all had walked past! Key Characteristics Cap: Infundibuliform (funnel-shaped) with a wavy margin. The cap surface is dry with fine scales and dark brown, gray, or black.

Hymenium: The spore bearing surface is smooth or slightly wrinkled and pale gray. This fungus lacks gills. Stipe: The stipe is a hollow cylinder that tapers down. Spore Print: Pale buff. Taking a spore print would be challenging due to the shape of the fungus. Ecology: Saprotrophic, getting its nutrients from decaying organic matter. This fungus is found in mixed conifer and hardwood forests in the spring. |

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed